If you are say, born close to the Millennial and Gen X divide, and you were a doll-loving child, you may have fond memories of Pleasant Company.

What was American Girl (née Pleasant Company)?

For those who did not read and reread the catalog: Pleasant Company was a project by a former educator and gift-giving aunt that became wildly successful.

(Later, the company rebranded as American Girl).

The project’s inventor, actually named Pleasant Rowland, had an notion to create dolls and books that were both the medicine and the spoon full of sugar.

(More on her and the company’s evolution in this Smithsonian piece.)

The medicine:

History lessons about American girlhood told through a series of historical fiction books focusing on a series of young girls. Each young girl brought to life different eras and contexts of American girlhood.

The project contained generous doses of 1980s feminism, egalitarianism, and civil rights.

Later, there was increasingly a focus on multiculturalism beyond European immigrants to the United States, particularly in the 1990s.1

The spoon full of sugar:

They were traditionally pretty dolls with clothing and accessories that brought the history lessons to life.

The clothes and accessories felt magically real.2

Inclusion gaps and attempts at reconciliation

Before we get into what was lost from the early era of Pleasant Company, a note on what was missing from the beginning: There were no non-Christian or ethnically non-European characters in the 1986 line-up.

This remained the case for seven years, during which time the company did introduce one other doll.

This first new doll was also ethnically European: Felicity Merriman, daughter of father descended from an English lord and a mother whose family owned a plantation with slaves.

The Felicity books did not meaningfully address the context of slavery around Felicity.

So, for those of us in the high school class of 2000 birth cohort (essentially the first cohort of girls to grow up with Pleasant Company), this period without a doll of color or a doll from a different religious tradition lasted until when we aged out of American Girl dolls.

Some forms of diversity were present; in fact, it was baked into the DNA of the project. One doll, “Samantha Parkington,” was born high New York high society; but WWII-era “Molly McIntire” was of Scottish descent and “Kirsten Larson” was a Swedish-born girl whose family was escaping famine.

But honoring the heritage of diverse European-descend girls was not the same as extending a hand to communities of color.

Over the next decade, Pleasant Company slowly added to its lineup of book series and accompanying dolls and accessories.

Of the final three historical dolls during the independent era of the company, two were girls of color, Addy Walker and Josefina Montoya.3

In 1998, Rowland sold Pleasant Company to Mattel. Soon, the company began to produce many more dolls, including historical characters that represented diverse communities, life experiences, and time periods.

In both the Rowland era and the Mattel era, the company made formal efforts to involve experts with a relationships to the diverse communities it was depicting, particularly with the historical dolls.

Nonetheless, criticism of the company has always been lively. And there have always been debates, and occasional controversy about its approach to representing diversity.

One example: At the start of the Mattel era, the company introduced a Native character, Kaya.

In doing so, they formally requested permission from the Nez Perce Tribe to create the doll, and created an advisory board to make decisions about it.

American Girl made a choice, for example, to create its first closed-mouth face mold since the other dolls’ face molds open-mouth expression would have had an inappropriate cultural meaning for the tribe.

Later, the brand used the same modified face mold for its first male doll, Logan, who was not Native. Critics argued that the company’s choice was insensitive and implied that a Native girl’s appearance was more masculine.

The brand will no doubt continue to receive a healthy amount of criticism as long as it remains popular—particularly given the ambitious nature of its mission to capture American girlhood, both historical and now also contemporary.

“THE” catalog

The American Girl books have been popular, but they were never quite as addictive as say, The Babysitter’s Club4 or the Sweet Valley High5.

But perhaps the most addictively readable text for girls of the 1980s and early 1990s was the Pleasant Company catalog itself.

I’m biased, but I consider that those last decades before the “screenification of everything” were a golden age of catalog copywriting.

In that Reagan / Bush 41 era, the likes of Hammacher Schlemmer and Lillian Vernon littered our bathroom floors and entryways, particularly leading up to the holidays.

Unlike much of today’s anemic catalog fare (Trader Joe’s quirky throwback style excepted), they were packed with words, words, words to captivate the reader.

The J. Peterman catalog’s product blurbs were so over the top they became an actual plot line on Seinfeld.

But for me, and perhaps for many girls, Pleasant Company was THE catalog.

In the movie Heat, a member of a criminal crew of thieves tells his boss, “the action is the juice.”

Meaning, the thrill of the heist is what he’s in it for, more so than the spoils.

Well, you know, for a certain type of girl, the catalog was the juice.

Why? This catalog occupied a highly underserved niche: It was a tour de force review of what social scientists would call the material culture of the historical characters lives.

Material culture is the stuff all around us, like the historical clothes, accessories, food, and decor, and furniture the Pleasant Company catalog featured.

One of the discipline’s major journals describes its focus this way:

Journal of Material Culture explores the relationship between artefacts and social relations. It draws on a range of disciplines including anthropology, archaeology, design studies, history, human geography and museology.

The Pleasant Company catalog was material culture studies made developmentally appropriate for children—and irresistible because it was miniature, and it was T-O-Y-S.

The Pleasant Company catalog was material culture studies made developmentally appropriate for children—and irresistible.

The recipe was simple: The educational books followed a formula that created opportunities to showcase culture, including material culture such as dress, food, and physical objects.6

Key contexts for that culture were topics that represented girls’ everyday life: home, school, food, toys, past-times, bedtime, birthdays, and the holidays (just Christmas, in those early years).

Each page of the catalog mirrored that formula, summarizing the book’s narrative and featuring a collection of artifacts that represented the key material culture in the books.

The school-focused catalog page showcased educational material culture. The holiday catalog page featured Christmas traditions. And so on.

Here is an example of how the catalogs worked, with the Swedish-born immigrant to Minnesota, “Kirsten Larson.”

(If you want to read through old versions of the catalogs, which I highly recommend, many have been scanned and posted online.)

Consider the vignette in the “Saint Lucia Gown” and “St. Lucia Wreath” copy on Kirsten’s Christmas Story page.

The blurbs educate about a Swedish cultural tradition for winter solstice centered on St. Lucia that also contains an important ceremonial role for girls.

They also connect the artifacts and tradition to the meaning for Kirsten: “Imagine how proud she’ll feel.”

Occasionally the catalog featured content contrasting the material culture of each girl, as in their school furniture collection.7

Now that you reflect on this, would it surprise you to find out that Pleasant Rowland, the founder of the company, had in fact not just been a teacher, but been a textbook writer?

This textbook writer figured out how to write a visually sumptuous textbook on historical girls’ material culture that reached a huge audience and was pored over like a sacred object.

This is not the only reason why she was able to sell the company in 1998 for $1.35 billion in today’s dollars; but it certainly speaks to a very particular set of skills.

An itch one can no longer scratch?

Perhaps like many moms born in the 1980s or early 1990s, I was impatient to revisit American Girl to find out if I wanted to share the catalog and dolls with my own children.

I finally did last year, when my elder child had become old enough.

My first step was ordering a catalog.

What I found was that the brand American Girl has long since decided to pursued dreams other than the catalog-as-historical-material-culture-textbook.

Today, a great emphasis of the company is on contemporary dolls and the ability to customize things like the eye color, skin tone, face shape, hair, and outfits.

Sound familiar? This a path set by a parent company, Mattel, that has learned how to keep Barbie both culturally central and a cash cow decade after decade.

Barbie is about contemporary fashion and variations in details like hair and eye color are a Barbie designer’s stock-in-trade.

No doubt many children and families prefer American Girl this way; after all, it is an even bigger business today with armies of young devotees.

And I won’t presume to argue that children somehow get less out of the company’s focus today.8

But I do mourn the lost greatness of the catalog-as-historical-materical-culture-textbook.

For in today’s American Girl world, the catalog has little room for the historical characters.

And, where the catalog does cover the historical characters, it does so without the dense copy that shared the girls’ stories and explained the meaning of their clothes and artifacts.

Here’s an example of how the catalog showcases a post-Mattel historical character, the 1970s “Julie.”

Note there’s barely any context about any of the fashion, furniture, or objects.

No attempt to to explain that, say, Julie’s macramé top (pictured on the right page below, in the bottom left image) is related to the 1970s counterculture interest in returning to handcraft.

Recapturing some of the old magic today

I haven’t been able to locate a company bidding for the specific territory that American Girl has ceded with dolls that are:

historical;

centered on girls;

focused on everyday material culture.

(And I’ll admit, it’s slow going to convince my artist friend to start an alternative company or get a consortium together to buy back the brand from Mattel.)

But, in the meantime, for your and my children, I have thought about a few other ways to scratch the itch:

The original Pleasant Company catalogs themselves.

You can buy the old catalogs on EBay, of course.

What I’d much prefer to do is buy a hardcover version of a selection of the early catalogs, but American Girl hasn’t seen fit to do that yet. As people with young kids know, catalogs are not known for their longevity and get lost easily in shelves.

Homemade historical toys

Then there’s creating one’s own historical dolls and artifacts, something my elder one already loves to do (though not yet with the historical angle).

Since we’re not seamstresses, that will mean things like homemade paper dolls and dioramas in the short term.

Books about material culture

Of course, there is a world of books and magazines out there that talk about tangible culture, particularly if you relax the constraints that it be about girls or children’s culture.

Here are some of our favorites. This is aggressively NOT a definitive or “all time best of Pleasant Company / American Girl catalog substitutes” list, but it has some fun starting points9:

📘 If You Come to Earth by Sophie Blackall

The conceit of this book is that a child is introducing the cultures of earth to an alien. Not dense in its text, as it is pitched at smaller children, but visually inventive.

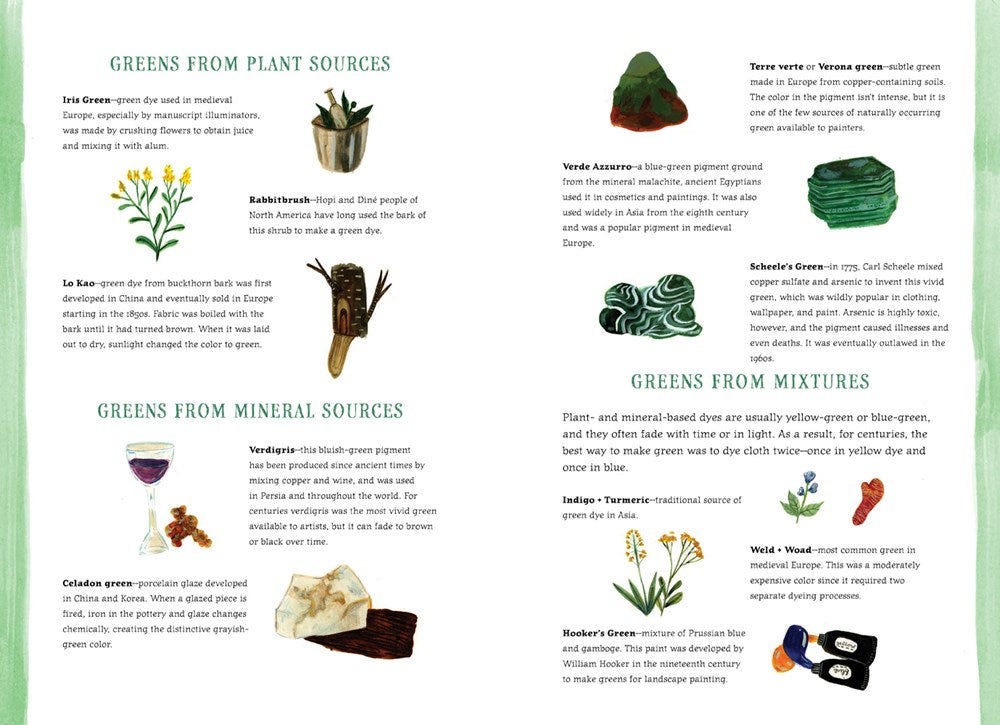

📘 Before Colors: Where Pigments and Dyes Come From by Annette Bay Pimentel

This is an invitingly illustrated book discussing the social history of pigments and dyes for children.

📘 Transported: 50 Vehicles that Changed the World by Matt Ralphs and Rui Ricardo

For nonfiction kids books about vehicles, of course, the book market is enormous and mostly very bloodless (and free of interesting information).

Transported is a very, very welcome break from the endless parade of context-less vehicle books.

For each vehicle, they describe its history and impact on society.

📘 Motel of Mysteries, Castle, and other works by David Macauley

Then there’s the oeuvre of polymath David Macauley, who is well-known for works like The Way Things Work but also investigations of physical culture, from high (say, Cathedral) to low (Toilets).

For older kids, perhaps they will be as beguiled as I was as a child with Motel of Mysteries.

This is not so much historical fiction as fiction that educates about how history is written (in particular, its pitfalls).

Read this fan account from the archeologist Scott Moore, distinguished university professor at IUP, suggesting your kids may be in danger of being heavily influenced by this book:

During my freshman year, I read Motel of the Mysteries by David Macaulay and ended up switching my major to classical archaeology. The book is a humorous, cleverly illustrated, satirical exploration of an archaeological excavation. As a freshman, I loved how clearly Macaulay demonstrated the pitfalls we create when we allow our own biases to shape our understanding of the past, and I began to reexamine how my own view of history was constructed. The book is as relevant today as it was then in making readers aware of the dangers of unexamined assumptions about the past, . . . and it is hilarious.

In case you’re curious

As a girl, the American Girl Dolls I had were: Kirsten (for the Little House-esque domestic culture, and those braids) and Samantha (for the New York connection, not to mention the gingerbread house and petit fours).

My neighbor had multiple dolls, including Felicity, too, and way more of the clothes accessories, so I got to admire them frequently.

(While we’re at it, if the Babysitter’s Club had had dolls, I would have had a Stacey, also the New Yorker. As for Sweet Valley, there was really no choosing, but if their had to have been a doll, it would have been the part-antihero, part-antagonist Jessica. Those identical lavalieres would probably have been very hard to execute well…)

For readers who are also prospective American Girl shoppers: my elder child enjoys “Rebecca Rubin,” a sort of a kid version of Funny Girl’s Fanny Brice.

Rebecca’s book series has Lower East Side New York Yiddish-speaking immigrant culture, musical theater, Passover, and costume design… fun things that are not exactly a dime a dozen when it comes to dolls and children’s lit.

One for you and the teens in your life

📘 All this thinking about everyday material culture made me want to finally read a book that’s been on my list for a while: The Structures of Everyday Life: Civilization and Capitalism 15th-18th Century Vol 1 by Fernand Braudel, a French historian born in 1902. (Written the same year as Motel of Mysteries, 1979.)

I can’t say I’m through it yet. I stand a better chance of finishing a three-stanza poem in between dinner and kid bedtime, than making headway a 623-page scholarly work.

But here’s a fun passage from his section on “costume and fashion” to give you a sense of what you’re in for:

If all the world were poor…

The question would not even arise. everything would stay fixed. No wealth, no freedom of movement, no possible change. To be ignorant of fashion was the lot of the poor the world over. Their costumes, whether beautiful of homespun, remained the same. The beautiful was represented by the feast-day costume, often handed down from parent to child. It remained identical for centuries on end, despite the infinite variety of national and provincial popular costumes. Crude homespun was the everyday working garb, made from the least expensive local resources: it varied even less.

And the illustrations! I enjoy this one, as I enjoy the notion of “cooking without bending down.” It seems entirely possible the the kitchen American Girl Kirsten Larson’s parents had back in the village in Sweden in the early 1850s was less well-equipped than this one from 1663!

Leading up to those changes, the company faced of outside pressure about the lack of representation of black and brown American girls. The first three dolls launched in 1986 were of European descent. The fourth and fifth dolls were African-American (a girl who escapes slavery) (1993) and a Mexican girl living in an area that later became part of New Mexico (1997).

The opposite of Barbie’s accessories, which were always a weak point for that brand.

At the time, the company also introduced its first contemporary character, a Jewish girl named Lindsey Bergman.

The Fellowship of the Ring[ing]… telephone for babysitting jobs.

What if your “black swan” were your actual twin?

Meet Samantha (or insert other doll name); Samantha Learns a Lesson; Samantha’s Surprise (holiday themed); Happy Birthday, Samantha; Samantha Saves the Day; and Changes for Samantha.

What a comics reader might think of as a crossover event.

Not least because I don’t know much about the new concepts and how children use them. Certainly if they’d been doing Disney or Broadway tie-ins when I was little, I would have begged for an Ariel doll. (Or campaigned for my generation’s misunderstood witch: Bernadette Peters.)

Thanks to my #1 influencer and personal librarian for a few of these recommendations.